In 2025, the use of Microsoft Windows 7 is not merely a matter of preference but a significant strategic decision with profound security, operational, and financial implications. This report concludes that for any internet-connected system, continued use of Windows 7 constitutes a critical and unjustifiable risk. Its viability is confined to highly specialized, isolated, and air-gapped environments where legacy dependencies are absolute and unavoidable. The operating system is fundamentally insecure, with the absence of security patches from Microsoft since January 2023 for most editions leaving it permanently vulnerable to OS-level exploits that modern antivirus and browsers cannot mitigate.

While a handful of critical applications—notably Firefox ESR and certain antivirus suites—still offer limited support, this ecosystem is fragile and shrinking. Reliance on this dwindling support is a temporary stopgap, not a long-term strategy. Community-driven efforts to bypass Microsoft’s Extended Security Update (ESU) licensing are illegal, inherently risky, and create a false sense of security by potentially introducing new vulnerabilities.

The only viable modernization path for Windows 7-era hardware is an upgrade to Windows 10. The stringent hardware requirements of Windows 11, such as Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0 and modern CPUs, render nearly all contemporary Windows 7 machines ineligible for the latest OS. Therefore, immediate migration to a supported operating system is the only responsible course of action for the vast majority of users. Continued use of Windows 7 should be treated as an exception-based risk, managed under strict isolation protocols.

Table: Windows 7 Viability Scorecard for 2025

| Assessment Criteria | Rating | Justification |

| Overall Security (Internet-Connected) | Critically Low | No OS security patches are available from Microsoft, leaving the system vulnerable to known and future exploits at the kernel level. |

| Software Compatibility (Web Browsers) | Low | Only two viable options remain: Mozilla Firefox ESR, which is frozen in features, and Supermium, a community-led project lacking corporate backing. |

| Software Compatibility (Antivirus) | Low | Support from major vendors is ending or ambiguous. The effectiveness of any antivirus is severely limited by the insecure underlying OS. |

| Hardware Driver Support | Critically Low | No new drivers are being developed for modern peripherals, effectively freezing the hardware capabilities of the system. |

| Official Microsoft Support | None | All official support channels, including the paid Extended Security Updates (ESU) program, have been terminated for mainstream editions. |

| Viability (Offline/Air-Gapped) | Moderate | Viable only if the system is physically and permanently isolated from all external networks and untrusted removable media. |

I. The State of Windows 7 in 2025: An Unsupported Legacy Platform

Defining “End of Life”: Beyond the Buzzwords

The term “End of Life” (EoL) is a definitive statement from a software vendor indicating the cessation of all active support. For Microsoft Windows 7, this process occurred in stages. Mainstream support, which included new feature development and non-security updates, concluded on January 13, 2015. Following this, the operating system entered an “extended support” phase, where it received only security patches. This phase officially ended on January 14, 2020, marking the point at which Windows 7 became unsupported for the general public. The period that followed was not a continuation of general support but a temporary, paid service for specific customers.

The Final Curtain: Deconstructing the End of Extended Security Updates (ESU)

Recognizing that many businesses could not immediately migrate away from Windows 7, Microsoft offered the Extended Security Update (ESU) program. Described as a “last resort option,” ESU provided paying commercial customers with “Critical” and “Important” security updates for up to three years past the 2020 EoL date. This program was available exclusively for Windows 7 Professional and Windows 7 Enterprise editions.

This final lifeline, however, has been severed. The ESU program for Windows 7 concluded definitively on January 10, 2023. As of 2025, there are no further official security patches available from Microsoft for these mainstream desktop versions. It is important to distinguish these versions from niche embedded systems; for example, Windows Embedded POSReady 7 has a separate ESU lifecycle that extends until October 8, 2024. This explains why some devices technically running a “Windows 7” core may still receive updates, but these are not the versions used by the general public or typical businesses.

The Myth of Unofficial Patches: Analyzing the Risks of ESU Bypasses

In the vacuum left by Microsoft, community-developed tools such as “BypassESU” have emerged. These utilities function by patching core system files, such as the Windows Update agent, to deceive Microsoft’s servers into delivering the now-discontinued ESU patches to unauthorized machines. While appealing on the surface, employing these tools is a deeply flawed and dangerous practice.

A multi-faceted risk analysis reveals severe drawbacks:

- Legality: These tools are explicitly illegal. They circumvent Microsoft’s licensing agreements to obtain a paid-for product for free, constituting software piracy.

- Security: The act of running an executable from an anonymous, untrusted source that modifies critical operating system files is a textbook security vulnerability. The tool itself could easily be bundled with malware, spyware, or a backdoor, compromising the very system it purports to protect.

- Reliability: The bypass mechanism is inherently fragile. Microsoft could, at any time, release a new Servicing Stack Update (SSU) or update to its validation checks that permanently breaks the tool. This has happened in the past, and it would leave users suddenly and unknowingly exposed without any notification.

- Completeness: The utility of these patches is also waning. As of late 2024, Microsoft had planned to cease releasing 32-bit (x86) versions of ESU patches, meaning any 32-bit Windows 7 systems using these bypasses would be left unprotected regardless.

The existence and use of these bypass tools have fostered a “zombie” ecosystem. Users install these patches under the belief that they are enhancing their security. In reality, they are introducing a new, unvetted dependency on anonymous developers and fundamentally altering the integrity of their operating system. This creates a paradox where the quest for security leads to the adoption of a practice that is fundamentally insecure. The result is a network of machines that appear patched but are built on a compromised and fragile foundation, representing an unknown and unpredictable threat vector. This state is arguably more dangerous than running an honestly unpatched machine, where the user is at least aware of the inherent risk.

II. The Case Against Continued Use: A Comprehensive Risk Analysis

The Unseen Threat: Operating System vs. Application-Level Vulnerabilities

The most critical misunderstanding among users of legacy systems is the belief that a third-party antivirus program can provide sufficient protection. This belief stems from a failure to distinguish between application-level threats and operating system-level vulnerabilities. An antivirus program is an application that runs on top of the operating system. It is effective at detecting and neutralizing malware, such as viruses or trojans, that attempt to execute as files or processes within the OS environment.

However, an antivirus program is powerless against an exploit that targets a fundamental flaw in the operating system’s core code, or kernel. If a hacker discovers a vulnerability in Windows 7’s networking stack, memory management, or driver model, they can gain control of the system at a privilege level beneath the antivirus software. This renders the security software blind and irrelevant. The situation is analogous to having a highly trained security guard (the antivirus) patrolling the hallways of a building, while the attacker possesses the master key to every door and can move through the walls (an OS exploit). No third-party software can patch these fundamental flaws; only the original vendor, Microsoft, can, and it no longer does for Windows 7.

Beyond Malware: Exposure to Ransomware, Botnets, and Zero-Day Exploits

Because Windows 7 is no longer receiving security updates, it has become a fixed, unchanging target for cybercriminals. Automated hacking tools and scripts constantly probe every corner of the internet, scanning for devices with known, unpatched vulnerabilities. A Windows 7 machine connected to the internet is a low-hanging fruit for these automated attacks.

Such a system is a prime candidate to be forcibly conscripted into a botnet, where its resources are used to conduct Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks or send spam without the owner’s knowledge. Furthermore, it is exceptionally vulnerable to ransomware, a type of malware that encrypts all personal data—documents, photos, financial records—and holds it hostage until a ransom is paid. Any new “zero-day” vulnerability discovered that affects the underlying architecture of Windows 7 will create a permanent, unfixable security hole, providing an open door for attackers for the remainder of the system’s life.

The Crumbling Ecosystem: Diminishing Software and Hardware Driver Support

The risks of using Windows 7 extend beyond direct security threats to include a rapid decline in operational viability. Software developers are increasingly dropping support for the aging OS, optimizing their products for modern platforms like Windows 10 and 11. While some older versions of popular applications, such as Adobe Photoshop 2020 or Microsoft Office 2016, may still function, users are permanently cut off from new features, performance enhancements, and critical security updates for those applications themselves.

Similarly, hardware manufacturers are no longer developing or validating Windows 7 drivers for new peripherals. Attempting to connect a modern printer, graphics card, webcam, or network adapter to a Windows 7 machine will likely result in failure or unstable performance. This effectively freezes the system in time, rendering it incompatible with the modern hardware ecosystem and limiting its long-term usefulness.

Compliance and Liability: The Business and Legal Implications

For businesses, non-profits, and any organization handling sensitive data, the use of an EoL operating system is not just a technical issue but a significant compliance and legal liability. Data protection regulations such as the GDPR in Europe or HIPAA in the United States mandate that organizations implement reasonable and appropriate security measures to protect personal information. Operating a system with known, unpatched vulnerabilities is a clear failure to meet this standard and could result in severe financial penalties in the event of a data breach.

Furthermore, financial institutions and other online services are increasingly taking steps to protect their ecosystems by blocking access from devices running unsupported operating systems. Continuing to use Windows 7 for sensitive activities like online banking or bill payment is explicitly and strongly discouraged by security experts and financial bodies alike, as it exposes personal financial data to an unacceptable level of risk.

III. The Niche Case for Continued Use: Legacy Systems and Strategic Isolation

When Upgrading Isn’t an Option: Critical Legacy Software Dependencies

Despite the overwhelming risks, there are specific, narrow scenarios where the continued use of Windows 7 is a necessity. The primary legitimate reason is the need to run “legacy” applications. These are often custom-built or highly specialized software packages, critical to business operations, that are incompatible with modern operating systems due to their reliance on deprecated system APIs or outdated architecture, such as 16-bit or 32-bit code. For some organizations, the cost and operational disruption of rewriting, replacing, or migrating data from this mission-critical software can be prohibitive, forcing them to maintain the legacy OS to support it.

Industrial and Embedded Systems: A Specialized Environment

A significant portion of legacy Windows 7 deployments exists within industrial and specialized environments. Industrial Control Systems (ICS), medical equipment, and manufacturing machinery often run on embedded versions of Windows that have been validated for a specific hardware and software configuration. These systems, such as Siemens’ SIMATIC PCS 7, have a much longer service life than consumer PCs. Upgrading the operating system on such a machine could break the proprietary control software, cause unpredictable behavior, and void the support contract with the equipment manufacturer, making it a non-viable option.

The “Air-Gap” Strategy: The Viability of Strictly Offline Usage

For these niche cases, the consensus among security professionals is that Windows 7 can be operated with a reasonable degree of safety only if it is completely and permanently disconnected from all untrusted networks, including the internet. This strategy is known as creating an “air gap”. An air-gapped machine is physically isolated, with no active Ethernet or Wi-Fi connection. This approach is suitable for running specific offline software, such as old video games or processing non-sensitive data, but it is entirely impractical for any task that requires web access.

However, maintaining a true air gap is more challenging than it appears. The strategy is often compromised by the need to transfer files or software to the isolated machine. This is typically done using removable media like a USB drive. If that USB drive has been connected to an internet-facing computer, it can become a vector for malware designed to spread through such media. A single infected file transferred to the air-gapped machine can breach the isolation and compromise the system without it ever directly touching the internet. This demonstrates that the air-gap strategy is not foolproof; its effectiveness depends on strict operational discipline and an understanding that its security is only as strong as its weakest link, which is often human behavior.

IV. Mitigation Strategies for Inescapable Deployment

For organizations where the immediate discontinuation of Windows 7 is not feasible, a multi-layered mitigation strategy is essential to reduce, but not eliminate, the inherent risks. This strategy focuses on securing the primary attack vectors: the web browser and endpoint vulnerabilities.

Layer 1: Securing the Browser

With Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Chromium-based browsers like Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge having long abandoned Windows 7, only two viable browser options remain for 2025.

Analysis: Mozilla Firefox Extended Support Release (ESR) 115

Mozilla Firefox stands as the last major browser to offer official support for Windows 7. Users on the legacy OS are automatically migrated from the standard release channel to Firefox version 115, which is an Extended Support Release (ESR). In a significant commitment to users on older platforms, Mozilla has extended security update support for ESR 115 until March 2026. This makes Firefox ESR the most stable and reliable browser choice for any remaining Windows 7 machine.

However, this support comes with significant limitations. Users are permanently locked into the feature set of version 115, which was originally released in mid-2023. They will not receive any new web platform features, performance optimizations, or user interface improvements that are introduced in newer versions of Firefox. Over time, this will lead to increasing compatibility issues as modern websites adopt newer web technologies not supported by the older browser engine. Furthermore, the ESR channel is generally considered less secure than the main release channel, as only high-risk security patches are typically backported.

Analysis: Supermium Browser

An alternative is Supermium, an open-source project that forks the modern Chromium browser and specifically recompiles it to run on legacy Windows versions, including Windows 7. Its primary advantage is providing access to a contemporary browsing engine (e.g., version 132 or newer as of late 2025) on an old OS. This includes support for the latest web standards and security features inherent to the Chromium platform. The project also pledges to maintain support for Manifest V2 extensions, such as the popular ad-blocker uBlock Origin, even after Google deprecates them in Chrome.

The primary limitation of Supermium is its origin. It is a community-driven project led by a single primary developer, lacking the vast resources, dedicated security teams, and rigorous auditing infrastructure of a major corporation like Mozilla or Google. Users of Supermium are placing their trust in a small team’s ability to keep pace with Chromium’s rapid release cycle and to patch critical vulnerabilities in a timely manner. While a commendable effort, it carries an implicit risk compared to an officially supported corporate product.

Layer 2: Endpoint Protection

While no antivirus (AV) can fix the underlying OS vulnerabilities, a currently supported AV solution is a critical component of any mitigation strategy.

Analysis of Antivirus Solutions with Stated Windows 7 Compatibility

- Bitdefender: This provider explicitly lists Windows 7 with Service Pack 1 in its official system requirements for consumer products. A key document regarding its business products provides a clear timeline: while new feature development for legacy Windows versions will cease in January 2025, Bitdefender will continue to provide security updates and maintenance releases until January 2026. This clear and extended support commitment makes Bitdefender a strong and reliable candidate.

- Norton: Norton’s support documentation consistently lists compatibility with Windows 7 with Service Pack 1 (SP1) and the necessary SHA2 update across its product line. However, the documentation does not specify a clear end-of-support date. This ambiguity presents a risk, as support could be terminated with little notice, but for now, it remains a compatible option.

- McAfee: The support status for McAfee products is highly contradictory and unreliable. One support article states that McAfee apps are “not officially supported on Windows 7” while simultaneously providing guidance for users on how to make them work with SP1. Another document explicitly lists Windows 7 under the “not supported” category. A separate document from Trellix (a McAfee enterprise offshoot) indicates extended support for some enterprise agents until 2026. This conflicting information makes McAfee an unsuitable and unreliable choice for any new or continued deployment on Windows 7.

The Inherent Limitations of Antivirus on an Unpatched OS

It must be reiterated that even the best antivirus software is only a layer of protection, not a foundational solution. It can effectively detect and block known malware files and monitor for suspicious application behaviors. However, it cannot patch an OS-level vulnerability. An exploit targeting a flaw in Windows 7’s kernel can execute before the AV has a chance to scan it or can operate at a privilege level that allows it to disable the AV software entirely.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of modern AV solutions is likely degraded on Windows 7. Modern antivirus technology has evolved far beyond simple signature-based scanning. It now heavily relies on advanced techniques like behavior-based detection, heuristics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to identify and block novel and zero-day threats. These advanced features often require deep integration with the modern Windows security architecture, utilizing components and APIs that are present in Windows 10 and 11 but are absent in Windows 7. Consequently, while a vendor may provide updated malware definitions for their Windows 7 client, the core engine’s most advanced and proactive protective features may be disabled or operate in a limited capacity. A user is therefore not just getting an AV on an old OS; they are likely getting a less effective version of that AV, further widening the security gap.

Table: Compatible Software Matrix for Windows 7 (2025)

| Category | Software Name | Latest Compatible Version | Stated Support End Date | Key Limitations & Risks |

| Browser | Mozilla Firefox ESR | 115.x | March 2026 | Receives security updates only; no new web features, performance improvements, or UI changes. Potential for future web incompatibility. |

| Browser | Supermium | 132.x (and newer) | Ongoing (Community-led) | Relies on a small development team; lacks corporate backing and rigorous, independent security auditing. |

| Antivirus | Bitdefender | Current Version | January 2026 (Security updates only) | Advanced detection features may be limited on Win7; cannot protect against OS-level exploits. |

| Antivirus | Norton | Current Version | Undefined | Support could be terminated without significant notice; cannot protect against OS-level exploits. |

| Antivirus | McAfee | N/A | Not Recommended | Support information is conflicting and unreliable, making it an unsuitable choice. |

V. Viable Upgrade Pathways and Modernization Strategies

For users committed to moving away from the risks of Windows 7, a clear and strategic upgrade path is necessary. The choice of destination is largely dictated by the capabilities of the existing hardware.

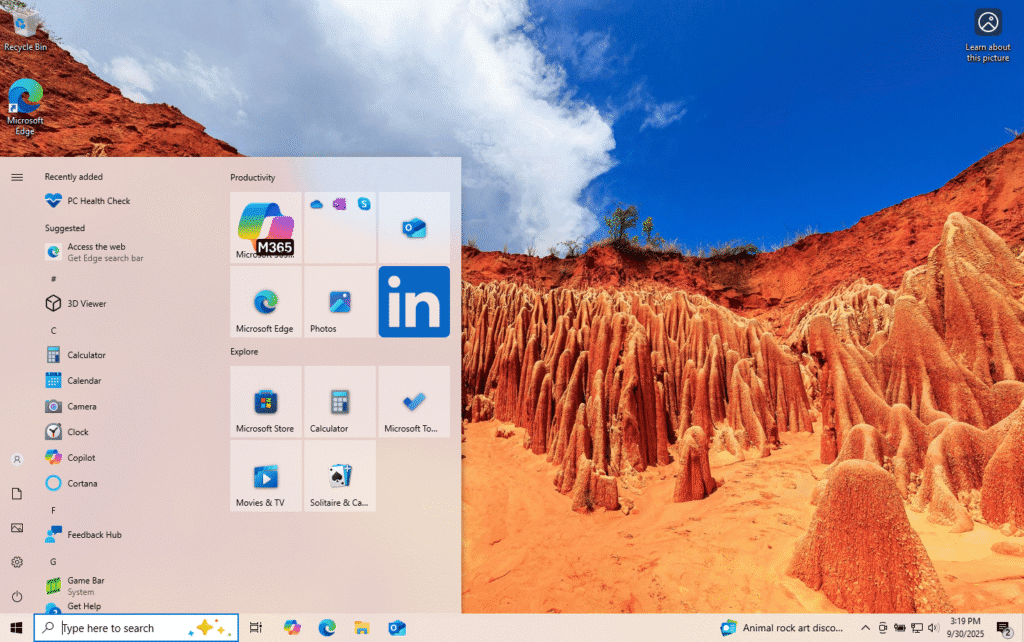

Path A: Transitioning to Windows 10

For the vast majority of systems currently running Windows 7, an upgrade to Windows 10 is the most logical and practical modernization step. The system requirements for Windows 10 are relatively modest—a 1 GHz processor, 1-2 GB of RAM, and 16-20 GB of storage space—specifications that most machines from the Windows 7 era can easily meet.

While Microsoft provided tools for an “in-place” upgrade that preserves user files and applications, a clean installation is strongly recommended for moving from an architecture as old as Windows 7. Over years of use, a Windows 7 system accumulates driver remnants, fragmented data, and potential system file corruption. An in-place upgrade can carry these issues over, leading to instability and poor performance on the new OS. A clean installation, which involves formatting the primary drive and installing Windows 10 from scratch, provides a stable, modern, and high-performance foundation. The process typically involves creating a bootable USB drive with the Microsoft Media Creation Tool, performing a full backup of personal data, and then booting from the USB to install the new OS.

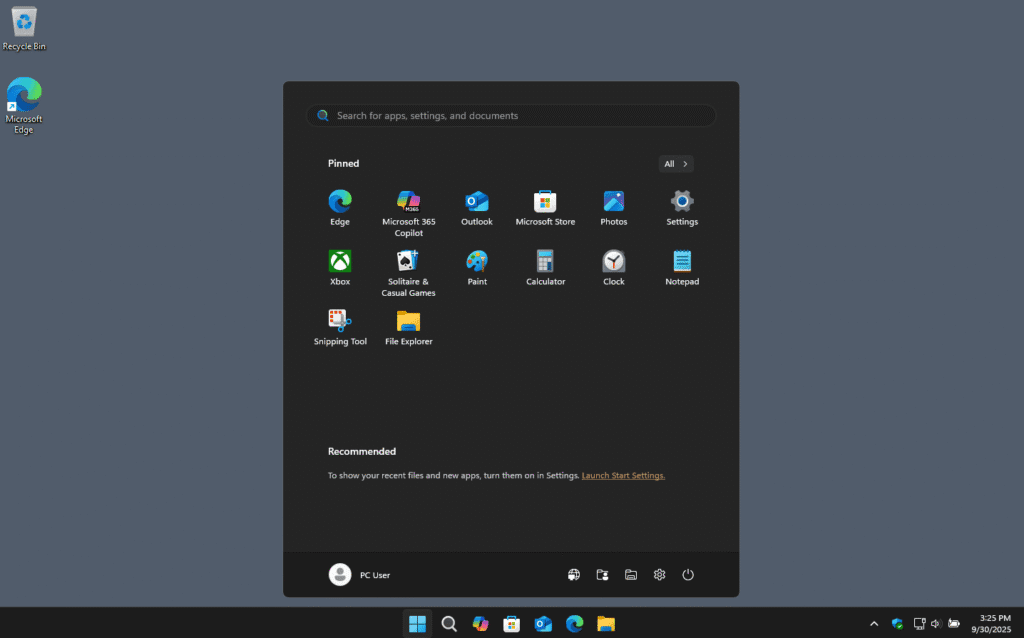

Path B: Assessing Viability for Windows 11

An upgrade to Windows 11 is not a feasible option for nearly all hardware that originally shipped with Windows 7. Windows 11 introduced a set of strict new hardware requirements that were not standard during the Windows 7 era, effectively creating a hard cutoff for older machines. The key disqualifying requirements include:

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0: A hardware-based security module that is rarely found on motherboards manufactured before approximately 2015.

- Secure Boot: A firmware security feature that requires a modern UEFI BIOS, as opposed to the legacy BIOS common on older PCs.

- Modern CPU: Microsoft officially supports only recent processor generations, generally 8th-generation Intel Core, AMD Ryzen 2000 series, and newer.

A PC from the Windows 7 era (2009-2015) will almost certainly lack a compatible CPU and a TPM 2.0 module, making a standard installation of Windows 11 impossible. Furthermore, there is no direct upgrade path from Windows 7 to Windows 11; a user would first have to upgrade to Windows 10 and then to Windows 11, but the hardware block remains the insurmountable obstacle.

Table: Upgrade Path Comparison from Windows 7

| Feature/Requirement | Upgrade to Windows 10 | Upgrade to Windows 11 |

| Direct Upgrade Path | Yes (though clean install recommended) | No |

| Hardware Compatibility | High (Most Win7 PCs meet minimum specs) | Critically Low (Requires modern CPU, TPM 2.0, Secure Boot) |

| Process Simplicity | Moderate | Complex (Requires intermediate upgrade and hardware validation) |

| Legacy Software Compatibility | Good (Excellent built-in compatibility modes) | Good (Similar to Win10, but driver support is less certain) |

| Microsoft Support End Date | October 14, 2025 (Paid ESU available) | At least 2027+ (Based on release cycle) |

| Recommendation | The only viable in-place software upgrade path. | Recommended only with the purchase of new, compliant hardware. |

VI. Final Analysis and Strategic Recommendations

The continued use of Windows 7 in 2025 presents a clear and present danger to data, privacy, and operational stability for any internet-connected device. The lack of security updates from Microsoft creates fundamental vulnerabilities that no third-party software can adequately address. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the risks, software ecosystem, and viable alternatives, the following tiered recommendations are provided.

Tier 1 Recommendation: For the General User and Most Businesses (Internet-Connected Use)

- Action: Cease all use of Windows 7 immediately.

- Justification: The security risks are unmitigable and far outweigh any perceived benefits of familiarity or avoiding upgrade costs. The potential for catastrophic data loss, financial theft, identity compromise, or ransomware infection is exceptionally high. The operating system should be considered inherently insecure by design.

- Pathway: For existing hardware that meets the minimum requirements, perform a clean installation of Windows 10. For hardware that is incompatible or nearing the end of its physical life, the most prudent course of action is to purchase a new computer with Windows 11 pre-installed.

Tier 2 Recommendation: For Organizations with Critical Legacy Dependencies (Isolated Network Use)

- Action: Physically disconnect the Windows 7 machine from the public internet. Isolate it on a segmented network (VLAN) with a strict, default-deny firewall policy that permits only the absolute minimum necessary traffic to a specific, trusted internal server required for its function.

- Justification: This strategy acknowledges the business-critical nature of the legacy software while containing the security risk to the greatest extent possible. The machine must be treated as a high-risk asset and should not be allowed to communicate with general-purpose workstations or the broader corporate network.

- Pathway: Implement the software mitigation stack outlined in this report (specifically Firefox ESR and Bitdefender) as a final layer of defense, but do not rely on it for primary security. The organization must aggressively pursue a modernization strategy for the legacy application, exploring options such as virtualization (running the Windows 7 environment in a secure virtual machine on a modern host OS) or budgeting for a full replacement of the software.

Tier 3 Recommendation: For Strictly Offline/Air-Gapped Systems

- Action: Ensure the machine has no physical or wireless network capability. Unplug any Ethernet cables and disable the Wi-Fi and Bluetooth adapters in the system’s BIOS/UEFI firmware.

- Justification: This is the only scenario where continued use of Windows 7 can be considered relatively safe from external, network-based threats.

- Pathway: A strict protocol must be established for introducing any external data. All removable media (e.g., USB drives, external hard drives) must be scanned for malware on a modern, fully patched, and protected machine before being used on the Windows 7 system. Users must accept that the system remains vulnerable to malware that spreads via this vector and that no sensitive, personal, or critical data should ever be stored on it.