Section 1: The End of an Era: Deconstructing the Windows 10 End-of-Support Lifecycle

The digital landscape is defined by cycles of innovation and obsolescence. For one of the most ubiquitous operating systems in history, Microsoft Windows 10, the cycle is nearing its conclusion. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the implications of continuing to use Windows 10 beyond its official end-of-support date, offering strategic guidance for individuals and organizations navigating this critical transition in 2025 and 2026.

1.1 The October 14, 2025 Deadline: Defining “End of Support”

Microsoft has definitively set October 14, 2025, as the end-of-support (EOS) date for Windows 10. It is critical to understand the precise technical meaning of this milestone. The operating system will not cease to function on this date; a PC running Windows 10 on October 15, 2025, will boot up and operate just as it did the day before. However, what will be irrevocably terminated is the ecosystem of support and maintenance that ensures the platform’s security and stability.

Specifically, after this date, Microsoft will no longer provide the following for Windows 10 :

- Security Updates or Fixes: This is the most critical cessation. Any security vulnerabilities discovered in the Windows 10 operating system after this date will not be patched, leaving the system permanently exposed to potential exploitation.

- Software and Feature Updates: The final feature update for Windows 10 was version 22H2. The OS is now feature-frozen, meaning it will receive no further enhancements or new capabilities.

- Technical Support: Microsoft customer service and technical support channels will no longer be available to assist with any issues related to Windows 10.

The fact that the OS continues to function creates a dangerous paradox. Users may perceive the immediate risk as low because their day-to-day experience is unchanged. This lack of immediate negative feedback can foster a false sense of security, leading to widespread user inertia. This complacency masks the invisible, accumulating risk of unpatched vulnerabilities, creating a massive, slow-boiling security crisis that threat actors will be poised to systematically exploit over time.

1.2 Immediate Consequences: The Cessation of Proactive Defense

The end of security patches marks a fundamental shift from a proactively defended to a passively vulnerable state. Every month, Microsoft releases security updates that patch dozens of newly discovered vulnerabilities. After October 14, 2025, this defensive wall crumbles for Windows 10 users. Any vulnerability found from that point forward becomes a “zero-day” exploit with no corresponding patch, effectively creating a permanent attack vector that threat actors can leverage indefinitely.

This cessation extends beyond the core operating system and has significant implications for Microsoft’s own software ecosystem.

- Microsoft 365 and Office Suite: For users of the subscription-based Microsoft 365 Apps, the situation is nuanced. While feature updates for these applications on Windows 10 will cease after August 2026 for Current Channel users, Microsoft will continue to provide critical security updates for the suite until October 10, 2028. This decision is not merely a courtesy; it is a strategic maneuver to safeguard the company’s significant recurring revenue from its flagship subscription service. It acknowledges the reality that millions of users cannot or will not upgrade their OS immediately and aims to keep them within the Microsoft 365 ecosystem. This creates a potentially confusing message for users: the underlying operating system is deemed insecure, but the premier application suite running on it will remain secured by its vendor for an additional three years.

- Non-Subscription Office Versions: The impact is more severe for users of perpetual Office licenses. Support for Office 2016 and Office 2019 will end entirely on October 14, 2025, across all operating systems. Newer versions, such as Office 2021 and Office 2024, will continue to function on Windows 10 but will be officially unsupported, meaning they will not receive updates or fixes in that configuration.

1.3 Market Impact: The Scale of the Forced Transition

The end of support for Windows 10 is not a minor event affecting a niche user base; it is a seismic shift impacting a colossal segment of the global computing market. Industry analysis suggests that nearly 200 million computers worldwide are currently running Windows 10 but are ineligible for the free upgrade to Windows 11, primarily due to Microsoft’s stringent hardware requirements.

Furthermore, user inertia is a powerful factor. A September 2025 study by cybersecurity firm Kaspersky revealed that over 53% of general users and nearly 60% of corporate users were still operating on Windows 10. This massive, slow-to-migrate user base represents a large, attractive, and dangerously homogenous target for cybercriminals. Once support ends, any exploit developed for Windows 10 will have a potential target pool of hundreds of millions of machines, making it a highly valuable and persistent vulnerability for attackers to focus on.

Section 2: Risk Analysis: A Multi-Faceted View of Operating an Unsupported System

Continuing to use Windows 10 after October 14, 2025, introduces a spectrum of risks that extend beyond simple malware infections. These risks are cumulative, impacting not only individual security but also business operations, legal compliance, and financial liability.

2.1 The Cybersecurity Threat Landscape: An Open Invitation to Attackers

The primary and most immediate risk is the drastically increased exposure to cybersecurity threats. Without a continuous stream of security patches from Microsoft, Windows 10 systems will become highly vulnerable to malware, ransomware attacks, data breaches, and unauthorized system access. Cybercriminals and threat actors actively monitor end-of-life dates for software and treat these unsupported systems as prime targets. They are aware that any security flaw discovered after the EOS date will remain unpatched, providing a stable and reliable exploit with an exceptionally long shelf life. The day after support ends has been described by industry experts as the beginning of an “open season” for hackers targeting Windows 10 machines.

The danger of this situation is not static; it grows at an accelerating rate. While on day one there may be no new, publicly known vulnerabilities, the security posture of the system degrades exponentially over time. As new flaws are discovered in the months and years that follow, they can be combined with previously known, unpatched vulnerabilities. This allows attackers to “chain” exploits—using one flaw to gain initial access and another to escalate privileges—creating attacks that are far more potent and damaging than the sum of their individual parts. This compounding effect makes the long-term use of an unpatched Windows 10 an untenable security position.

2.2 Operational Degradation and Software Incompatibility

Beyond the direct security threats, users of Windows 10 will experience a gradual but inevitable decay of the system’s functionality and performance. As the global software ecosystem moves forward, third-party software developers and hardware manufacturers will progressively drop support for the obsolete operating system. This will manifest in several ways:

- Application Incompatibility: New versions of popular software may refuse to install or run on Windows 10. For example, major vendors like Adobe have shown a tendency to support only the most recent versions of Windows, a trend that will certainly accelerate post-EOL.

- Hardware Driver Failures: Manufacturers of new peripherals (printers, graphics cards, etc.) will no longer develop or test drivers for Windows 10, leading to compatibility issues and preventing users from taking advantage of modern hardware.

- System Instability: As other software and drivers evolve, they may expect OS-level updates that Windows 10 will never receive, leading to unpredictable behavior, system crashes, and increased downtime.

Essentially, Windows 10 will become a digital island, frozen in its 2025 state while the rest of the technological world sails on, leading to increasing operational friction and a degraded user experience.

2.3 Compliance, Legal, and Insurance Implications

For businesses and professional organizations, the risks transcend technical issues and enter the realms of legal and financial liability. Many industry regulations and data protection laws—such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in healthcare, the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) for financial transactions, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe—explicitly or implicitly require organizations to maintain up-to-date, patched, and vendor-supported systems to protect sensitive data.

Operating Windows 10 beyond its EOS date can place an organization in direct violation of these mandates, leading to severe consequences:

- Failed Audits and Penalties: A compliance audit could reveal the use of unsupported software, resulting in failed certifications and substantial financial penalties.

- Invalidated Cyber Insurance: Most cyber insurance policies contain clauses requiring the insured to maintain “reasonable security standards.” Running an unsupported operating system is a clear failure to meet this standard and can be used as grounds to deny a claim in the event of a data breach, leaving the business to bear the full financial brunt of the incident.

- Legal Negligence: In the event of a data breach originating from an unsupported Windows 10 machine, the organization could be found legally negligent for failing to take basic steps to secure its infrastructure, dramatically increasing its legal jeopardy and potential damages.

For these organizations, the EOS date acts as a compliance time bomb. The moment support ends on October 15, 2025, they are technically out of compliance. While the negative consequences—a failed audit, a denied insurance claim, or a lawsuit—may not manifest for months or even years, the liability is incurred instantly.

Section 3: Strategic Pathways Forward: A Comparative Analysis of Your Options

With the end of support for Windows 10 being a certainty, users and organizations must choose a strategic path forward. The decision involves a trade-off between cost, effort, security, and long-term viability. The following table provides a high-level comparison of the primary options available.

| Option | Security Level | Estimated Consumer Cost | Estimated Business Cost (per device) | Implementation Effort | Hardware Dependency | Long-Term Viability |

| Upgrade to Windows 11 | High | $0 (Free upgrade) | $0 (Free upgrade) | Low to Medium | High (Strict requirements) | High |

| Pay for ESU | Medium | $0 to $30 (Year 1 only) | $61 to $427 (Up to 3 years) | Low | Low (Uses existing hardware) | Low (Temporary) |

| Migrate to Linux | High | $0 | $0 | High | Low (Runs on old hardware) | High |

| Migrate to ChromeOS Flex | High | $0 | $0 | Medium | Low (Runs on old hardware) | High |

| Purchase New PC | High | $400+ | $600+ | Low | N/A | High |

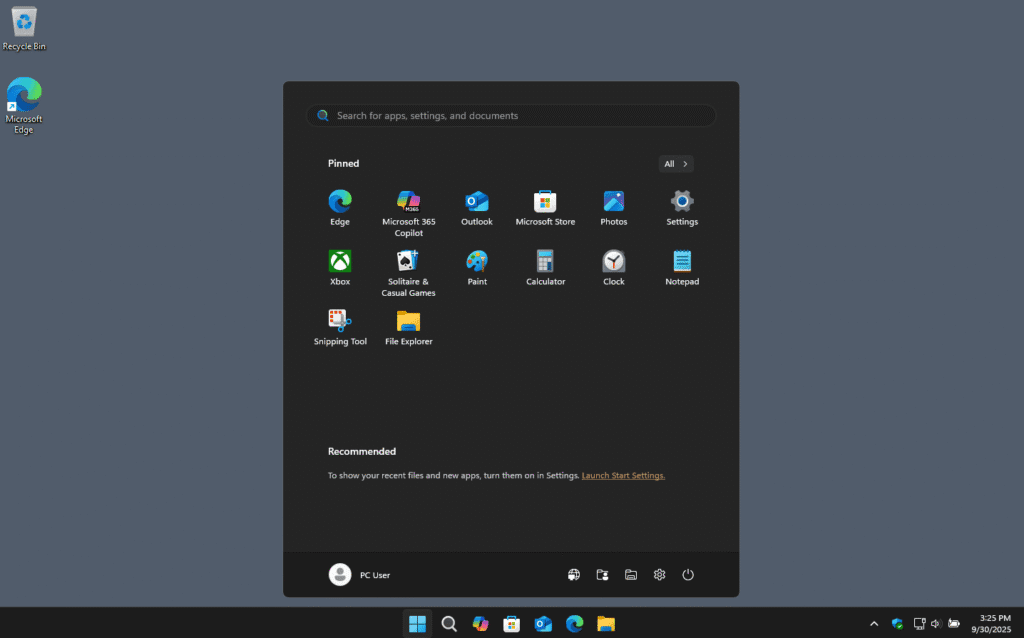

3.1 The Primary Path: Migration to Windows 11

For users with compatible hardware, the most direct and recommended path is to perform a free in-place upgrade to Windows 11. This modern operating system is designed with heightened security as a core principle and will receive full support from Microsoft for years to come. However, the viability of this path is entirely dependent on meeting a strict set of hardware requirements that have rendered millions of older PCs ineligible.

3.1.1 In-Depth Hardware Requirements Analysis

Microsoft’s system requirements for Windows 11 are not arbitrary; they are intended to establish a higher, more secure baseline for the entire Windows ecosystem. The key requirements that often act as blockers are:

- Processor (CPU): The system must have a 1 gigahertz (GHz) or faster processor with two or more cores. Crucially, the CPU must appear on Microsoft’s official lists of compatible 64-bit processors, which generally includes 8th-generation Intel Core processors and newer, AMD Ryzen 2000 series and newer, and select Qualcomm SoCs.

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM): Version 2.0 of the TPM is a mandatory requirement for an official installation. A TPM is a secure crypto-processor that provides hardware-based security functions, such as generating and storing cryptographic keys, which is essential for features like BitLocker and Windows Hello.

- System Firmware: The PC must support UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) and be Secure Boot capable. UEFI is the modern replacement for the legacy BIOS system and enables more advanced security features, including Secure Boot, which helps prevent malicious software from loading during the system’s startup process.

- RAM and Storage: A minimum of 4 GB of RAM and a 64 GB or larger storage device are required. While these are the official minimums, a satisfactory user experience, especially with multitasking, generally requires 8 GB of RAM or more.

These stringent requirements effectively create a two-tiered user base: the “compatibles,” who have a free and straightforward upgrade path, and the “incompatibles,” a massive group forced into more complex, costly, or risky decisions. This bifurcation is the central driver of the entire EOS challenge.

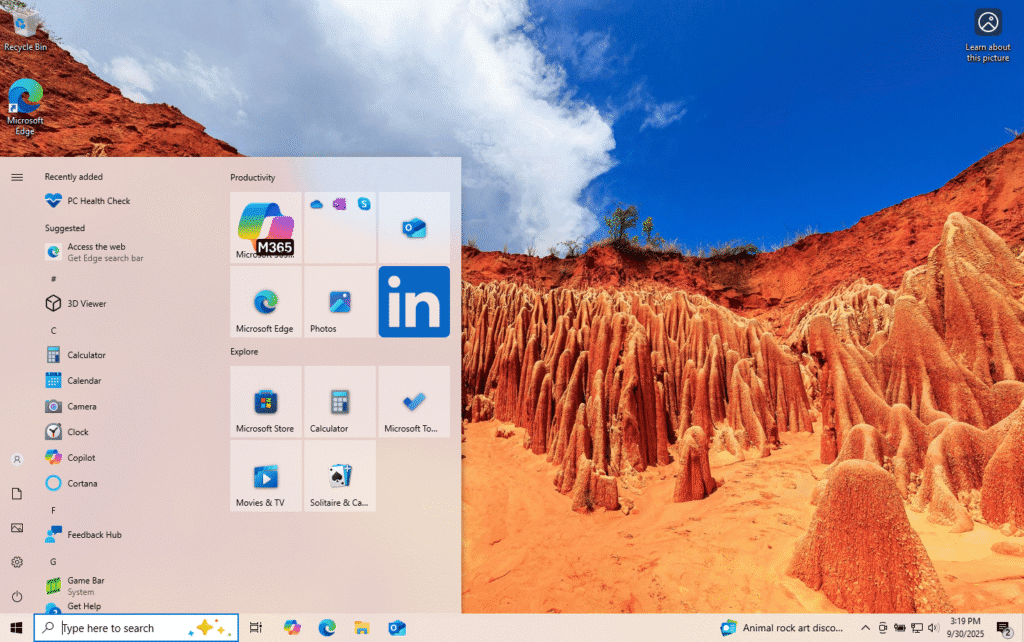

3.1.2 A Practical Guide to Assessing System Compatibility

Users can determine their PC’s eligibility for the Windows 11 upgrade through several methods:

- Microsoft PC Health Check App: This is the simplest and most user-friendly method. Microsoft provides this free application, which, when run, performs a comprehensive scan of the system’s hardware and reports whether it meets the requirements for Windows 11, identifying any specific components that fall short.

- Manual Verification: More technically proficient users can manually check the key requirements. TPM status can be verified by running tpm.msc in the Run dialog. The system’s firmware mode (UEFI or Legacy BIOS) and Secure Boot status can be checked within the system’s firmware settings, typically accessed by pressing a specific key (e.g., F2, Del) during startup.

3.1.3 Evaluating Unofficial Installation Methods

For hardware that is officially incompatible, a community of enthusiasts has developed workarounds. Tools like Rufus can create a Windows 11 installation USB drive that is modified to bypass the TPM 2.0 and CPU compatibility checks during the setup process. While this can allow Windows 11 to be installed on older machines, it is a high-risk strategy. Microsoft explicitly states that such configurations are unsupported. While these systems may receive updates initially, Microsoft provides no guarantee of future compatibility, and a future Windows update could potentially render the system unstable or unbootable. This path should only be considered by experts who understand and accept the associated risks.

3.2 The Lifeline for Legacy Hardware: Alternative Operating Systems

For the millions of users with hardware that cannot run Windows 11, replacing the entire operating system is a highly viable and secure alternative. This approach should be viewed not as a niche technical exercise but as a legitimate security strategy that directly resolves the core problem of running an unpatched OS.

3.2.1 Deep Dive: Linux Distributions

Linux offers a powerful, secure, and entirely free alternative. Modern Linux distributions have evolved significantly and are no longer solely the domain of developers. Several “distros” are specifically designed to be lightweight and provide a familiar user experience for those transitioning from Windows.

- Linux Mint: Often cited as one of the best choices for Windows converts, Linux Mint offers a polished and intuitive desktop environment (Cinnamon) that closely resembles the Windows 7/10 layout. It is built on a stable Ubuntu base and comes with a comprehensive suite of pre-installed software for productivity and media consumption.

- Linux Lite: As its name suggests, Linux Lite is designed to be lightweight and run efficiently on older hardware. It uses the XFCE desktop environment, which is fast and resource-friendly, and provides a simple, clean interface that is easy for newcomers to navigate.

- Other Lightweight Options: For extremely old or low-spec machines, distributions like Puppy Linux (which can run entirely from system RAM) or Bodhi Linux offer even more minimal resource usage, breathing new life into hardware that would otherwise be destined for recycling.

3.2.2 Deep Dive: Google ChromeOS Flex

For users whose computing needs are primarily web-based (e.g., email, social media, streaming, online documents), Google’s ChromeOS Flex presents a compelling option. It is a free, cloud-first operating system designed to be fast, simple, and secure. Key advantages include extremely fast boot times, automatic background updates, and a security architecture based on sandboxing that makes it highly resistant to traditional malware.

Installation is straightforward via a USB drive, and the minimum system requirements are modest: an Intel or AMD x86-64 bit processor, 4 GB of RAM, and 16 GB of internal storage. However, there is a critical limitation to be aware of: unlike the version of ChromeOS that ships on new Chromebooks, ChromeOS Flex does not support the Google Play Store or Android apps. This means the software ecosystem is limited to web applications and Linux applications (on supported models).

3.3 The Inevitable Option: Planning for Hardware Replacement

The most straightforward, albeit most expensive, solution is to purchase a new PC that comes with Windows 11 pre-installed. This path eliminates all compatibility concerns and ensures the user benefits from the performance, efficiency, and security enhancements of modern hardware that was designed to work in concert with a modern operating system. Many retailers offer trade-in or recycling programs that can help offset the cost and responsibly dispose of old equipment For businesses, replacing PCs that are more than a few years old is often the most economically sound decision in the long run, especially when factoring in the risks and potential costs of a security breach on an outdated machine.

Section 4: The Stopgap Measure: A Critical Evaluation of the Extended Security Updates (ESU) Program

Recognizing the challenge posed by the large number of incompatible PCs, Microsoft has introduced the Extended Security Updates (ESU) program for Windows 10. This program is designed as a temporary, paid-for lifeline, allowing users and organizations to continue receiving security patches for a limited time while they plan their migration. It is crucial to view ESU as a transitional bridge, not a permanent solution.

4.1 Program Mechanics: Duration, Scope, and Limitations

The ESU program provides only “Critical” and “Important” security updates, as defined by the Microsoft Security Response Center. It does not include any new features, non-security bug fixes, design changes, or access to technical support. The duration of the program varies by user segment:

- Consumers: The ESU program is available for one year only, extending security updates until October 13, 2026.

- Businesses and Educational Institutions: These organizations have the option to purchase ESU for up to three years, extending support to October 2028.

The existence of this program will create a fragmented security landscape after October 2025. There will not be a single security state for Windows 10; rather, there will be multiple co-existing tiers: fully vulnerable unpatched systems, consumer systems patched for one year, and enterprise systems patched for up to three years. This fragmentation complicates security management and creates distinct classes of targets for attackers, who will likely focus their efforts on the largest and most vulnerable group: the unpatched machines.

4.2 Cost-Benefit Analysis for Different User Segments

The pricing structure for the ESU program is not uniform; it is strategically tiered to influence the behavior of different user groups. This pricing is a deliberate behavioral nudge from Microsoft.

- Consumers: The list price is $30 for the single year of eligibility. However, Microsoft offers two ways to obtain it for free: by using the Windows Backup feature to back up files and settings to a Microsoft Account/OneDrive, or by redeeming 1,000 Microsoft Rewards points. This effectively makes the program free for most engaged consumers, a tactic to keep them within the Microsoft ecosystem.

- Educational Institutions: The pricing is heavily subsidized, costing just $1 per device for the first year, $2 for the second, and $4 for the third. This acknowledges the tight budget constraints in the education sector.

- Enterprise/Commercial Businesses: The cost is substantial and designed to be a strong financial disincentive against long-term use. The price is $61 per device for the first year, which then doubles to $122 for the second year, and doubles again to $244 for the third year. The total three-year cost of $427 per device is punitive and intentionally designed to make upgrading hardware or migrating to Windows 11 a more economically rational decision.

4.3 Enrollment Procedures and Prerequisites

For consumers, enrollment in the ESU program is handled directly through the Windows Update settings panel in Windows 10. The system will present an option to “Enroll now” as the EOS date approaches. A key prerequisite for consumers is that they must be signed in with a Microsoft Account to activate and maintain the ESU subscription, even if they are paying the $30 fee. This requirement reinforces Microsoft’s strategy of integrating its services more deeply into the user experience.

Section 5: The Software Ecosystem on Borrowed Time: Browsers and Antivirus Analysis

For those who choose to continue using Windows 10, the functionality and security of third-party applications, particularly antivirus software and web browsers, become paramount. While vendors of these critical applications have signaled continued support, this creates a potentially dangerous illusion of security.

5.1 Antivirus Software: A Necessary but Insufficient Defense

A robust, up-to-date antivirus (AV) solution is an absolute necessity for any Windows 10 machine used after the EOL date. However, it is fundamentally incapable of replacing the security updates provided by the operating system vendor.

5.1.1 The Critical Distinction: Threat Detection vs. Vulnerability Patching

It is essential to understand the different roles played by AV software and OS security patches. Antivirus programs work primarily by using signature-based detection to identify and block known malware, and heuristics to detect suspicious behaviors indicative of a malicious process. They are a reactive defense against threats that are attempting to execute on the system.

OS security patches, in contrast, are a proactive defense that fixes fundamental flaws or vulnerabilities within the operating system’s code itself. An unpatched OS vulnerability can be exploited by an attacker to gain deep system access, potentially allowing them to bypass or disable the antivirus software entirely before it can even detect a threat. Relying solely on an antivirus on an unpatched OS is akin to hiring a security guard to patrol a building while leaving a window permanently unlocked. The security of the entire system is only as strong as its weakest link, which will unequivocally be the unpatched Windows 10 kernel.

5.1.2 Vendor Support Deep Dive

Major antivirus vendors have indicated their intention to continue supporting Windows 10 users, recognizing the large, persistent market.

| Vendor | Stated Support End Date | Official Policy Source | Key Limitation |

| Avast | October 2028 | Official Support FAQ | Cannot patch underlying OS vulnerabilities; provides threat detection only. |

| Norton | Not officially stated; likely long-term | Community Forums | Cannot patch underlying OS vulnerabilities; provides threat detection only. |

| McAfee | Not officially stated; confirmed to continue | Official Support Page | Cannot patch underlying OS vulnerabilities; provides threat detection only. |

| Kaspersky | Not officially stated; likely long-term | Press Releases/Forums | Cannot patch underlying OS vulnerabilities; provides threat detection only. |

- Avast: Has officially committed to providing extended support for its security apps on Windows 10 through October 2028.

- Norton: While no formal EOL date for Windows 10 support has been announced, community moderators and historical precedent (long-term support for Windows XP and Vista) strongly suggest that support will continue for the foreseeable future. However, Norton representatives are clear that their product cannot compensate for the lack of OS security updates.

- McAfee: Has officially confirmed that its products will continue to function and receive virus definition and product updates on Windows 10 after the EOL date, as its software is maintained independently of the Microsoft lifecycle.

- Kaspersky: Has not provided a definitive end date but has issued statements emphasizing the risks of using an EOL OS while recommending its products with “exploit prevention technologies” as a mitigating factor, implying continued support. Company forums indicate support will continue for a long time, as current versions still support Windows 7.

5.1.3 Pros and Cons of Relying on Third-Party AV

- Pros: An up-to-date AV provides an essential, non-negotiable layer of defense against the vast majority of common malware, phishing attempts, and other known threats. It is the first line of defense against newly emerging malware variants.

- Cons: It can create a dangerous false sense of total security. It is fundamentally unable to protect the system from exploits that target unpatched, kernel-level vulnerabilities in the Windows 10 operating system.

5.2 Web Browsers: The Primary Attack Surface

The web browser is the modern user’s primary interface with the internet and, consequently, the single largest attack surface on any computer. Keeping the browser updated is critical, but its security is intrinsically linked to the health of the underlying OS.

5.2.1 Vendor Support Deep Dive

Fortunately for Windows 10 users, major browser developers plan to continue support long after the 2025 EOL date. For many users, the true EOL of an OS occurs when essential applications like browsers stop working. The extended support timelines from these vendors will prolong the functional life of Windows 10, but also the period of high risk.

| Browser | Stated Support End Date | Key Risk |

| Microsoft Edge | At least October 2028 | High. An exploit can bypass browser security by targeting an unpatched OS-level vulnerability (e.g., sandbox escape). |

| Mozilla Firefox | “Several years” away; no date set | High. An exploit can bypass browser security by targeting an unpatched OS-level vulnerability (e.g., sandbox escape). |

| Google Chrome | “Not yet scheduled” | High. An exploit can bypass browser security by targeting an unpatched OS-level vulnerability (e.g., sandbox escape). |

- Mozilla Firefox: Mozilla has made a firm public commitment to continue supporting Windows 10 on both its standard Release and Extended Support Release (ESR) channels for “several years” to come, with no end date currently announced.

- Microsoft Edge: As a Microsoft product, Edge has a clear and generous support timeline on Windows 10. It will continue to receive security and feature updates until at least October 2028. Significantly, a device does not need to be enrolled in the ESU program to receive these Edge updates.

- Google Chrome: Google’s official enterprise support page lists the deprecation date for Windows 10 as “Not yet scheduled,” which implies that support will continue for a significant period post-EOS, given the browser’s dominant market share.

5.2.2 The Inherent Risk: The Browser-to-OS Exploit Chain

A modern web browser is not a fully self-contained application. It relies heavily on the underlying operating system for critical security functions, including memory management, process isolation (sandboxing), and handling the network stack. This dependency creates a critical point of failure on an unpatched OS.

A sophisticated attack can use a two-stage process: first, an exploit targets a vulnerability within the browser itself to gain initial code execution. Then, a second exploit targets a known, unpatched vulnerability in the Windows 10 OS to “escape” the browser’s protective sandbox and gain full control over the system. There are real-world precedents for this type of attack; a known Chrome vulnerability was found to be exploitable only on Windows 7 because it required a second, OS-level flaw in that unsupported system to work effectively. An up-to-date browser on an out-of-date OS is a house with a steel door and paper walls.

5.2.3 Pros and Cons of Using a Modern Browser on an Obsolete OS

- Pros: A continuously updated browser is vital. It protects against the thousands of web-based threats that target the browser directly, such as malicious scripts and phishing websites, and it maintains compatibility with evolving web standards.

- Cons: It cannot secure the operating system it runs on. The browser’s own security mechanisms, like its sandbox, are fundamentally capped by the security of the OS kernel. It remains the largest attack surface, and its integrity is contingent on the integrity of the unpatched system beneath it.

Section 6: Synthesis and Strategic Recommendations

The end of support for Windows 10 presents a complex decision point for millions of users. The optimal path forward depends on the user’s technical proficiency, budget, hardware capabilities, and tolerance for risk. The following framework provides tailored recommendations for distinct user profiles.

6.1 Decision-Making Framework for Key User Personas

- The Non-Technical Home User: For users who rely on their computer for daily tasks like banking, shopping, and communication but are not technically inclined, security and simplicity are paramount.

- Primary Recommendation: If the hardware is compatible, perform the free upgrade to Windows 11. If not, the most secure and hassle-free option is to purchase a new, affordable PC or a ChromeOS device. The risk of operating an unmanaged, insecure system is too great to justify continuing with Windows 10.

- Secondary Option: Enroll in the one-year ESU program (ideally via the free methods) to provide a one-year window to plan for a new device purchase.

- The Technical Power User/Hobbyist: This user is comfortable with advanced configurations and understands the security landscape.

- Primary Recommendation: Upgrade to Windows 11 if compatible. For incompatible hardware, a migration to a user-friendly Linux distribution like Linux Mint is a strong, secure, and cost-effective option.

- Secondary Options: The one-year ESU program is a viable stopgap. Continuing to use Windows 10 without ESU is strongly discouraged but acknowledged as technically possible for an expert who employs meticulous safe computing practices (e.g., running in a limited user account, avoiding risky downloads, using a robust firewall) and maintains a rigorous, offline, full-image backup strategy. This path carries a high cognitive load and significant residual risk.

- The Small Business Owner: For this profile, the decision is driven by operational continuity, data security, and legal/financial liability.

- Primary Recommendation: A time-bound, mandatory migration plan to upgrade or replace all workstations to run Windows 11 is the only responsible course of action. The risks of non-compliance with data protection regulations (like PCI-DSS or HIPAA) and the potential for a cyber insurance claim to be denied are unacceptable business risks.

- Secondary Option: The ESU program should be viewed as an expensive, temporary measure used only for mission-critical systems tied to legacy software or hardware that cannot be immediately replaced. Its punitive pricing structure should be used as leverage to gain budget approval for a full hardware refresh.

- The Enterprise IT Administrator: This role requires a strategic, fleet-wide approach to migration.

- Primary Recommendation: Initiate a formal, phased migration project to Windows 11. Utilize endpoint management tools like Microsoft Endpoint Manager (Intune) or Lansweeper to conduct a fleet-wide compatibility assessment.

- Strategic Use of ESU: The exponentially increasing cost of the ESU program should be presented to leadership not as an operational expense but as a clear financial indicator that hardware replacement is the more prudent long-term investment. ESU should be procured only for a small, well-defined subset of legacy systems where the cost of migration exceeds the cost of the updates.

6.2 Tiered Recommendations: From Most Secure to Highest Risk

Synthesizing the analysis, the available options can be ranked into tiers based on their overall security posture:

- Tier 1 (Most Secure): Decommission old hardware and purchase a new PC with Windows 11 pre-installed. This provides the benefits of both a modern, supported OS and modern, secure hardware.

- Tier 2 (Secure): Upgrade compatible hardware to Windows 11. For incompatible hardware, migrate the system to a supported Linux distribution or ChromeOS Flex. Both paths result in a fully patched and supported operating system.

- Tier 3 (Temporary Mitigation): Remain on Windows 10 but enroll in the Extended Security Updates (ESU) program. This mitigates the most critical risks for a limited time but does not address OS stagnation or third-party software support decay.

- Tier 4 (High Risk): Remain on Windows 10 without ESU, relying on a constantly updated third-party antivirus suite, a modern web browser, and extremely cautious user behavior. This approach leaves the system fundamentally vulnerable to any OS-level exploit.

- Tier 5 (Unacceptable Risk): Continue using Windows 10 with no mitigating controls (e.g., no ESU, outdated AV). This is a negligent approach that will almost certainly lead to system compromise.

6.3 Final Verdict on the Long-Term Viability of Windows 10

The evidence is conclusive: while Windows 10 may remain functional for several years beyond its October 2025 end-of-support date, largely due to the extended support timelines of third-party browser and antivirus vendors, it is not a viable or secure long-term platform. The cessation of security updates from Microsoft creates a foundational weakness that no third-party application can fully remedy. Over time, the cumulative security debt of unpatched vulnerabilities will become insurmountable, and the operational friction from an aging, increasingly incompatible software ecosystem will render the operating system obsolete in practice.

The decision facing users is not if they must migrate away from Windows 10, but rather when and how they will manage that inevitable transition. Proactive planning and decisive action before or shortly after the deadline are the most effective strategies to ensure a secure, stable, and productive computing future.